Town in Dagestan, Russia

| Izberbash Izberbash | |

| City [1] | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Kumyk | Yiz bir bash |

| Welcome sign at the entrance to the city | |

| Coat of arms | |

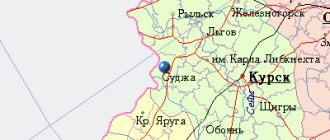

| Location of Izberbash | |

| Izberbash Location of Izberbash Show map of Russia Izberbash Izberbash (Republic of Dagestan) Show map of Republic of Dagestan | |

| Coordinates: 42°33′48″N 47°51′49″E / 42.56333°N 47.86361°E / 42.56333; 47.86361 Coordinates: 42°33′48″N 47°51′49″E / 42.56333°N 47.86361°E / 42.56333; 47.86361 | |

| A country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Dagestan [1] |

| Based | 1932 |

| City status from | 1949 |

| Square [2] | |

| • General | 22.55 km 2 (8.71 sq mi) |

| Height | 0 m (0 ft) |

| population size (2010 Census) [3] | |

| • General | 55 646 |

| • Evaluate (2018) [4] | 58 690 ( + 5,5% ) |

| • Classify | 297th place in 2010 |

| • Density | 2,500/km2 (6,400/sq mi) |

| Administrative status | |

| • Subordinate | Izberbash city [1] |

| • Capital from | G. Izberbash [1] |

| Municipal status | |

| • Urban district | Izberbash urban district [5] |

| • Capital from | Izberbash urban district [5] |

| Timezone | UTC+3 (MSK[6]) |

| Postal code [7] | 368500–368502 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 87245 |

| OKTMO ID | 82715000001 |

| Web site | www.mo-izberbash.ru |

Izberbash

(Russian: Izberbash, Kumyk: Yiz bir bash, Hizbirbaş [8]) is a city in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia, located on the shores of the Caspian Sea 56 km (35 mi) southeast of Makhachkala, the capital of the republic. Population: 55,646 (2010 census); [3] 39,365 (2002 census); [9] 28,122 (1989 census). [10]

Demographics[edit]

Ethnic groups in the urban administrative area (2002 census): [11]

- Dargins (65.4%)

- Kumyks (14.4%)

- Lezgins (7.3%)

- Russians (5.1%)

- Avars (2.8%)

- Lucky (2.0%)

- Azerbaijanis (1.0%)

Ethnic groups in the city itself (2002 census): [12]

- Dargins (64.9%)

- Kumyks (14.8%)

- Lezgins (7.5%)

- Russians (5.3%)

- Avars (2.6%)

- Lucky (1.9%)

- Azerbaijanis (1.0%)

Excerpt characterizing Izberbash

It was already dark, and Pierre could not make out the expression that was on Prince Andrei’s face, whether it was angry or tender. Pierre stood silently for some time, wondering whether to follow him or go home. “No, he doesn’t need it! “Pierre decided to himself, “and I know that this is our last date.” He sighed heavily and drove back to Gorki. Prince Andrey, returning to the barn, lay down on the carpet, but could not sleep. He closed his eyes. Some images were replaced by others. He stopped at one for a long time, joyfully. He vividly remembered one evening in St. Petersburg. Natasha, with a lively, excited face, told him how last summer, while out picking mushrooms, she got lost in a large forest. She incoherently described to him the wilderness of the forest, and her feelings, and conversations with the beekeeper whom she had met, and, interrupting every minute in her story, she said: “No, I can’t, I’m not telling it like that; no, you don’t understand,” despite the fact that Prince Andrei reassured her, saying that he understood, and really understood everything she wanted to say. Natasha was dissatisfied with her words - she felt that the passionately poetic feeling that she experienced that day and which she wanted to turn out did not come out. “This old man was such a charm, and it was so dark in the forest... and he was so kind... no, I don’t know how to tell,” she said, blushing and worried. Prince Andrey smiled now with the same joyful smile that he smiled then, looking into her eyes. “I understood her,” thought Prince Andrei. “Not only did I understand, but this spiritual strength, this sincerity, this spiritual openness, this soul of hers, which seemed to be connected by her body, I loved this soul in her... I loved her so much, so happily...” And suddenly he remembered about how his love ended. “He didn’t need any of this. He didn't see or understand any of this. He saw in her a pretty and fresh girl, with whom he did not deign to throw in his lot. And I? And he is still alive and cheerful.” Prince Andrei, as if someone had burned him, jumped up and began to walk in front of the barn again. On August 25, on the eve of the Battle of Borodino, the prefect of the palace of the French Emperor, Mr. de Beausset, and Colonel Fabvier arrived, the first from Paris, the second from Madrid, to Emperor Napoleon in his camp near Valuev. Having changed into a court uniform, Mr. de Beausset ordered the parcel he had brought to the emperor to be carried in front of him and entered the first compartment of Napoleon's tent, where, talking with Napoleon's adjutants who surrounded him, he began to uncork the box. Fabvier, without entering the tent, stopped, talking with familiar generals, at the entrance to it. Emperor Napoleon had not yet left his bedroom and was finishing his toilet. He, snorting and grunting, turned now with his thick back, now with his overgrown fat chest under the brush with which the valet rubbed his body. Another valet, holding the bottle with his finger, sprinkled cologne on the emperor’s well-groomed body with an expression that said that he alone could know how much and where to spray the cologne. Napoleon's short hair was wet and tangled over his forehead. But his face, although swollen and yellow, expressed physical pleasure: “Allez ferme, allez toujours...” [Well, even stronger...] - he said, shrugging and grunting, to the valet who was rubbing him. The adjutant, who entered the bedroom in order to report to the emperor about how many prisoners were taken in yesterday's case, having handed over what was needed, stood at the door, waiting for permission to leave. Napoleon, wincing, glanced from under his brows at the adjutant. “Point de prisonniers,” he repeated the adjutant’s words. – Il se font demolir. “Tant pis pour l’armee russe,” he said. – Allez toujours, allez ferme, [No prisoners. They force themselves to be exterminated. So much the worse for the Russian army. Well, even more, well, stronger...] - he said, hunching his back and exposing his fat shoulders. - C'est bien! Faites entrer monsieur de Beausset, ainsi que Fabvier, [Good! Let de Bosset come in, and Fabvier too.] - he said to the adjutant, nodding his head. - Oui, Sire, [I'm listening, sir.] - and the adjutant disappeared through the door of the tent. Two valets quickly dressed His Majesty, and he, in a blue guards uniform, walked out into the reception room with firm, quick steps. At this time, Bosse was hurrying with his hands, placing the gift he had brought from the Empress on two chairs, right in front of the Emperor’s entrance. But the emperor got dressed and went out so unexpectedly quickly that he did not have time to fully prepare the surprise. Napoleon immediately noticed what they were doing and guessed that they were not yet ready. He didn't want to deprive them of the pleasure of surprising him. He pretended not to see Monsieur Bosset and called Fabvier over to him. Napoleon listened, with a stern frown and in silence, to what Fabvier told him about the courage and devotion of his troops, who fought at Salamanca on the other side of Europe and had only one thought - to be worthy of their emperor, and one fear - not to please him. The result of the battle was sad. Napoleon made ironic remarks during Fabvier's story, as if he did not imagine that things could go differently in his absence. “I must correct this in Moscow,” said Napoleon. “A tantot, [Goodbye.],” he added and called de Bosset, who at that time had already managed to prepare a surprise by placing something on the chairs and covering something with a blanket. De Bosset bowed low with that French court bow, which only the old servants of the Bourbons knew how to bow, and approached, handing over an envelope. Napoleon turned to him cheerfully and pulled him by the ear. – You were in a hurry, I’m very glad. Well, what does Paris say? - he said, suddenly changing his previously stern expression to the most affectionate. – Sire, tout Paris regrette votre absence, [Sire, all of Paris regrets your absence.] – as it should, answered de Bosset. But although Napoleon knew that Bosset had to say this or the like, although he knew in his clear moments that it was not true, he was pleased to hear it from de Bosset. He again deigned to touch him behind the ear. “Je suis fache, de vous avoir fait faire tant de chemin,” he said. - Sire! Je ne m'attendais pas a moins qu'a vous trouver aux portes de Moscou, [I expected no less than to find you, sir, at the gates of Moscow.] - said Bosset. Napoleon smiled and, absentmindedly raising his head, looked around to the right. The adjutant approached with a floating step with a golden snuff-box and offered it to her. Napoleon took it. “Yes, it happened well for you,” he said, putting the open snuffbox to his nose, “you love to travel, in three days you will see Moscow.” You probably didn’t expect to see the Asian capital. You will make a pleasant trip. Bosse bowed with gratitude for this attentiveness to his (until now unknown to him) inclination to travel. - A! what's this? - said Napoleon, noticing that all the courtiers were looking at something covered with a veil. Bosse, with courtly dexterity, without showing his back, took a half-turn two steps back and at the same time pulled off the coverlet and said: “A gift to your Majesty from the Empress.” It was a portrait painted by Gerard in bright colors of a boy born from Napoleon and the daughter of the Austrian emperor, whom for some reason everyone called the King of Rome. A very handsome curly-haired boy, with a look similar to that of Christ in the Sistine Madonna, was depicted playing in a billbok. The ball represented the globe, and the wand in the other hand represented the scepter. Although it was not entirely clear what exactly the painter wanted to express by representing the so-called King of Rome piercing the globe with a stick, this allegory, like everyone who saw the picture in Paris, and Napoleon, obviously seemed clear and liked it very much. “Roi de Rome, [Roman King.],” he said, pointing to the portrait with a graceful gesture of his hand. – Admirable! [Wonderful!] – With the Italian ability to change his facial expression at will, he approached the portrait and pretended to be thoughtfully tender. He felt that what he would say and do now was history. And it seemed to him that the best thing he could do now is that he, with his greatness, as a result of which his son played with the globe in a bilbok, should show, in contrast to this greatness, the simplest fatherly tenderness. His eyes became misty, he moved, looked back at the chair (the chair jumped under him) and sat down on it opposite the portrait. One gesture from him - and everyone tiptoed out, leaving the great man to himself and his feelings. After sitting for some time and touching, without knowing why, his hand to the roughness of the glare of the portrait, he stood up and again called Bosse and the duty officer. He ordered the portrait to be taken out in front of the tent, so as not to deprive the old guard, who stood near his tent, of the happiness of seeing the Roman king, the son and heir of their beloved sovereign.

Climate[edit]

Izberbash has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk

).

| Climate data for Izberbash | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | October | But I | December | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3,9 (39,0) | 4,3 (39,7) | 7,7 (45,9) | 14,5 (58,1) | 21,1 (70,0) | 26,3 (79,3) | 29,2 (84,6) | 28,8 (83,8) | 24,0 (75,2) | 17,7 (63,9) | 11,3 (52,3) | 6,5 (43,7) | 16,3 (61,3) |

| Daily average °C (°F) | 0,8 (33,4) | 1,3 (34,3) | 4,5 (40,1) | 10,5 (50,9) | 17,0 (62,6) | 22,1 (71,8) | 25,2 (77,4) | 24,7 (76,5) | 20,1 (68,2) | 14,1 (57,4) | 8,2 (46,8) | 3,6 (38,5) | 12,7 (54,8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | -2,2 (28,0) | -1,6 (29,1) | 1,3 (34,3) | 6,6 (43,9) | 12,9 (55,2) | 17,9 (64,2) | 21,2 (70,2) | 20,6 (69,1) | 16,3 (61,3) | 10,6 (51,1) | 5,2 (41,4) | 0,8 (33,4) | 9,1 (48,4) |

| Average precipitation, mm (inches) | 23 (0,9) | 31 (1,2) | 22 (0,9) | 20 (0,8) | 29 (1,1) | 24 (0,9) | 26 (1.0) | 24 (0,9) | 40 (1,6) | 46 (1,8) | 33 (1,3) | 32 (1,3) | 350 (13,7) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org [13] | |||||||||||||

Administration

The city of Izberbash is located on the Caspian lowland, on the picturesque coast of the Caspian Sea, 65 km south of the capital of the Republic of Dagestan, Makhachkala, on a strip of plain (up to 4.5 km) between the sea and the Izberg-Tau mountain, connecting Northern and Southern Dagestan, near the spurs Greater Caucasus. Since ancient times, this strip served as a trade caravan route and one of the directions of the great route. Federal railways and highways pass through the city. Izberg railway station was built in 1900 (currently Izberbash station).

Izberbash is a multinational city, the population is about 60 thousand people. Mostly Dargins, Kumyks, Lezgins, and Russians live here.

Natural conditions are characterized by short, not cold and windy winters with a minimum temperature in January of up to -17 degrees Celsius, and hot summers with a maximum temperature in July of up to + 37.7 degrees. The average annual temperature is +13 degrees Celsius. The predominant wind direction is northwest, less often southeast. Average wind speed is 5 m/s. Precipitation per year ranges from 200 to 400 mm. Natural resources include oil, gas, thermal waters, and limestone.

Among the representatives of the animal world, hedgehogs and turtles live within the city, and there are snakes and rodents. The sea is home to valuable species of fish: sturgeon, beluga, stellate sturgeon, kutum, mullet, herring and others; endemic Caspian seals live on the coastal ridges.

The history of the settlement begins in 1931, when the first tent was erected near the station by workers who were conducting preparatory work for the development of oil fields.

In 1932, by order of the People's Commissar of Heavy Industry of the country, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, all geological exploration work for oil and gas in Dagestan was entrusted to the Grozneft trust, whose geological service was headed by I.O. Brod, in the future - head. Department of Moscow State University, which has done a lot for the study and development of the oil regions of Dagestan.

In 1935, the first exploration wells revealed the commercial oil and gas potential of the Achi-su area, and a number of exploration wells were drilled in Izberbash. By order of the Grozneft trust dated May 9, 1935, the Dagneftegazrazvedka office was organized, which included the exploration areas: Izberbash, Achi-su, Uytash, Kayakent, Khoshmenzil.

And on April 12, 1936, exploration well No. 8 - Izberbash produced the first commercial oil with a flow rate of 250 tons per day from a depth of 1650 m from the Chokrak sediments. The discovery of an oil field in Izberbash marked the beginning of the emergence and development of an oil field, which gave birth first to a workers' village, and then to a city - the first-born of the oil industry of Dagestan.

Industry professionals from Izberbash made a great contribution to the development of the oil and gas industry: brothers G. and M. Azizov, Sh. Abdulmukminov, M. Akayev, A. Ali-Ada, M. Abeydullaev, N. Valovoy, M. Gadzhiev, I. Gunashev , Kh. Klychev, B. Magomedov, E. Ozerina, A. Saidov, S. Sovzikhanov, I. Ermurzaev, I. Kurbanov, M. Magomedov and many others.

Subsequently, the main oil pipeline “Grozny-Makhachkala-Achisu-Izberbash-Dagestan Ogni-Derbent” was built.

By Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR No. 761/5 dated June 1, 1950, on the proposal of the Supreme Council of the DASSR dated April 2, 1948. Izberbash was transformed into a city of republican subordination.

For many years, Izberbash was rightfully considered a city of oil workers and machine builders. On the basis of repair and mechanical workshops for servicing oil fields here, in the post-war years, a powerful city-forming enterprise “Dag ZETO ” for the production of thermal furnaces was created, which became the head enterprise in the Dagelektroterm VPO system.

In place of swamps and swamps, the young city of Dagestan, Izberbash, now stretches along the shore of the Caspian Sea. It continues to be built. The city streets, sidewalks, squares and alleys have high-quality improved coating. Dozens of multi-storey and many beautiful individual residential buildings, industrial enterprises and cultural institutions, hotels, and recreation centers have been built on the shores of the Caspian Sea.

The city has the State Musical and Drama Theater named after O. Batyrai, the Palace of Culture, a cinema, and a local history museum.

Mechanical engineers have mastered and are producing a number of consumer goods. More than a dozen large and medium-sized enterprises operate and produce food and light industry products, among them there are already widely known enterprises in the republic and Russia, such as: CJSC "Wine-Cognac", LLC "Confectionery Factory" Dagintern, LLC "Novopak", LLC " Eurasia", LLC "Kolos", garment factory named after Imam Shamil, etc.

Izberbash residents have taken and are taking an active part in the life of the country. They helped to harvest a rich virgin harvest, built the Baikal-Amur Mainline, the Chirkey hydroelectric power station, participated in the liquidation of the consequences at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, and helped victims of devastating earthquakes in Armenia and other regions of the country. And now many oil specialists from Izberbash work in other cities and regions of Russia and abroad, where oil and gas are produced.

The name of the city has a special history. According to one version, until 1895, the territory where the city is located was a deserted, swampy place. The Germans, who were building a railway through the territory of the present city, paid attention to the mountain that forms the profile of a person, and said that work was being carried out in the area where there was a mountain (Das istberg). So the railway station was named Eastberg (Izberg). A series of rocks of the Izberg-Tau mountain, at an altitude of 150 meters above sea level, overlapping each other form a resemblance to the silhouette of Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin, which was first noticed by the famous French writer Alexandre Dumas, who was traveling on a stagecoach to Derbent while traveling through the Caucasus. Local residents added “bash” to the word “Izberg”, which means head, and the village began to be called Izberbash.