| City of Tyrnyauz Kabardian-Cherk. Tyrnauz karach.-balk. Tyrnyauz

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrnyauz Moscow |

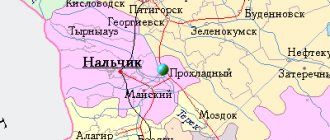

| Nalchik Tyrnyauz |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1934

Tyrnyauz

(Karach-Balk. Tyrnyauz) is a city in the Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria. The administrative center of the Elbrus region and the urban settlement of Tyrnyauz.

Geography

The city is located in the southwestern part of the republic, on both banks of the Baksan River, 90 km southwest of the city of Nalchik and 40 km northeast of Mount Elbrus. Through Tyrnyauz, along the valley of the Baksan River, the Baksan-Elbrus highway runs, leading to the foot of Mount Elbrus.

The area of the urban settlement is 61 km2. Of these, the city limits account for about a quarter of the area.

It borders with the lands of settlements: Bylym in the north and Verkhniy Baksan in the south.

The city is located in the mountainous part of the republic, at an altitude of more than 1,300 meters above sea level, and is one of the highest located cities in Russia. The relief is an area rugged by ridges, with narrow gorges in river valleys. The entire city is located in the valley of the Baksan Gorge. The highest point of the urban settlement is Mount Toturbashi (2786 m). The elevation changes are significant and range from 1500-2000 meters.

The subsoil of the territory of the urban settlement is rich in deposits of tungsten, molybdenum, building gypsum, various types of marble (including black), high-strength granite gneisses, facing granites, talc, feldspathic raw materials, roofing slates, aplite (porcelain stone), argallite clays, lime and other useful fossils. The volume of profitable reserves of the Tyrnyauz deposit can provide up to one third of the needs of the Russian economy for tungsten-molybdenum raw materials.

The hydrographic network within the city is represented by the Baksan and Girkhozhan-su rivers, as well as smaller streams flowing from the ridges. There are springs and deposits of mineral waters.

The climate is moderate. Due to the proximity of the mountains and location in the gorge, the climate in the city differs sharply from the climate of the foothills and plains of the republic. At the beginning of spring, with sharp changes in temperature, strong dry winds (foehn) blow from the mountains. The average temperature ranges from +16.5°C in August to -4.5°C in winter. The average annual air temperature is 6.5°C. The average annual precipitation is about 850 mm.

Does the city have a future?

In 2015, in the Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria, work began on the reconstruction of the city of Tyrnyauz and regional roads that lead to Elbrus and the city of Nalchik.

The city of Tyrnyauz is considered the face of the Elbrus region, since the Elbrus-Baksan road passes through it, which leads to the foot of the mountain.

For a long time the settlement was desolate, and finally its reconstruction began. Regional authorities allocated money for the restoration and repair of monuments, streets and houses.

At present, the issue with the mining plant and its administrative buildings, which are in a terrible state of disrepair, has not yet been resolved. To demolish them, additional funding is needed, but there is no free money in the budget yet.

A project has been developed for the construction of a mining and metallurgical complex in a populated area. He would revive the dying city of Tyrnyauz in Kabardino-Balkaria and provide jobs for the working population. But the project has not yet been implemented. The city is gradually falling into decay.

What does the future hold for him? What will happen to him in ten years? What will happen to the younger generation? These issues are relevant not only for the city of Tyrnyauz, but also for all small towns in Russia. And there are no answers to them yet.

Etymology

According to J. N. Kokov, the toponym is translated from the Karachay-Balkar language as “crane gorge”, where the turna

- “crane”,

auz

- “gorge”.

The name “crane gorge” is justified by the fact that during low clouds and fog, cranes fly low over the river along the gorge (this was reported by local resident Yu. M. Murzaev, who often observed this phenomenon). According to P. S. Rototaev, the name of the toponym contains the Balkar element tyrna

- “scratch” (

tyrnauuch

- “harrow”, “rake”).

Before the city was built, this area was a fairly wide valley, abundantly littered with pebbles. It looked like terrain through which a harrow had passed at a considerable depth. Obviously, subsequently the word tyrnauuch

, or the word

auz

was added to the word

tyrna

- “gorge”, “gorge”, since there is a gorge higher up the gorge. Thus, the toponym can be translated as “harrowed gorge.” This name is sometimes translated as “gorge of the winds,” although there is no reason for this[2].

Attractions

The sights of the city of Tyrnyauz in the Elbrus region are few. The city's buildings are mostly one-story, as well as 3-4-story buildings. But there are also several high-rise buildings that were built in the 50s of the 20th century. Industrial buildings are located in a steep cliff.

There are no historical buildings or structures in the city; all its development was carried out in the 20th century.

During the Great Patriotic War, 16,000 Balkars (30% of the Balkar population) took part in the fight against the Nazi invaders. In honor of them, a stele was erected in the city center and the Eternal Flame was lit.

A special place in the city is occupied by a modest monument, which is located on the top above the city. This is the obelisk of Flerova Vera. The monument is dedicated to the discoverers of ore deposits in these places.

Story

The city was founded as the village of Girkhozhan in 1934, during the discovery of the Tyrnyauz tungsten-molybdenum deposit[3].

In 1937, construction of the first plants began in the upper reaches of the Baksan Gorge. In the same year, the village of Girkhozhan was renamed into the working village of Nizhny Baksan.

In 1955, the village of Nizhny Baksan received city status and was renamed Tyrnyauz. In 1963, the city received the status of a city of republican (ASSR) subordination.

In 1994, Tyrnyauz was transferred to a city of regional subordination and transformed into the administrative center of the newly formed Elbrus region.

With the collapse of the USSR and the closure of the Tyrnyauz molybdenum plant, the number of residents began to decline rapidly, and the city lost a third of its population during the census period from 1989 to 2002. A series of mudslides in 2000 also contributed to the rapid decline in the city's population.

Currently, the city's population continues to slowly decline. Attempts are being made to restore the tungsten-molybdenum plant to return the city to its former significance (there is a plan to build a 95 km long railway line from the Soldatskaya station [4], which should greatly contribute to the said restoration of the mining and processing plant).

Education, health and culture

The city's educational institutions include 4 primary and 3 secondary schools, a gymnasium and a lyceum. In addition, there is one created for children with disabilities. Here we provide assistance to parents in raising such children.

Health care institutions in the city include a dental clinic, a district clinic and a district hospital.

Among cultural institutions, the Center for National Crafts, the Central Library, a local history museum and a stadium for 2,500 people open their doors here.

Tyrnyauz tragedy

On July 18, 2000, at 23:15, a powerful mudflow poured from the Girkhozhan tract onto Tyrnyauz[5]. According to the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations, as a result of mudflows on July 18 and 19, residential buildings were flooded and a road bridge across the river was destroyed. Baksan. Due to the threat of another mudflow, it was decided to temporarily resettle the residents of three houses. In total, 930 people were resettled from damaged houses. The forces of the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations restored the pedestrian bridge in the central part of the city, and also installed a pontoon bridge across the river. Gerkhozhan-Su. The complex of measures taken made it possible to restore the life support system. During the mudflows, 8 people died and 8 were hospitalized[6]. Almost 40 people were listed as missing[7].

Local government

The structure of local government bodies of urban settlements is:

- And about. Head of the local administration of the urban settlement of Tyrnyauz - Chimaev Takhir Mussaevich

- The local administration (executive and administrative body) is the administration of the urban settlement of Tyrnyauz.

The apparatus of the local administration of the urban settlement consists of 15 people.

- The representative body is the Local Government Council of the urban settlement of Tyrnyauz. Consists of 19 deputies.

The head of the urban settlement of Tyrnyauz is the Chairman of the Local Government Council - Tolgurov Rasul Abdulkerimovich.

Streets

Autogarage 1

| Autogarage 2 |

| Atabia Etezova |

| Baysultanova |

| Baksanskaya |

| Balkarskaya |

| Balkarskaya 2 |

| Verkhniy Aul |

| Vinogradova |

| Factory |

| Zarechnaya |

| Kolkhoznaya |

| Mizieva |

| Mira |

| Michurina |

| Musukaeva |

| Embankment |

| Nogmova |

| Otarova |

| Razin |

| Rogacheva |

| Soviet |

| Elbrussky Avenue |

| Eneeva |

| Etezova |

Notable natives

- Kokov Valery Mukhamedovich (1941-2005) - the first president of Kabardino-Balkaria.

- Konyaev Igor Gregorevich (1963) - Russian theater actor, director, laureate of the State Prize of Russia.

- Akhmatova Lyubov Chepeleuovna (1971) is a famous Balkar poetess, member of the Union of Writers of Russia.

- Zumakulova Tanzilya Mustafaevna (1934) - Balkarian poetess.

- Akkaev Khadzhimurat Magomedovich is a Russian weightlifter, medalist of the Olympic Games in Athens and Beijing.

- Kuramagomedov Zaur Ismatulaevich - Russian Greco-Roman wrestler, two-time champion of Russia, bronze medalist of the World and European Championships, bronze medalist of the 2012 Olympics in London

Notes

- Suyunchev Kh. I., Urusbiev I. Kh. Russian-Karachay-Balkar dictionary. About 35,000 words. M.: “Soviet Encyclopedia”, 1965. P. 744.

- Kabardian-Russian dictionary. 20,000 words / Ed. B. M. Kardanova. M.: State Publishing House of Foreign and National Dictionaries, 1957. P. 487.

- ↑ 12

The permanent population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian). Date accessed: April 27, 2021. Archived May 2, 2021. - Law of the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic of February 27, 2005 N 13-RZ “On the status and boundaries of municipalities in the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic” (Russian). docs.cntd.ru.

_ Date accessed: October 7, 2021. - For the first time in 25 years, a cinema opened in the highest mountainous city in Russia

. - Moscow is big, Sochi is long. Rating of the “best” cities in Russia (unspecified)

. - Kokov J. N.

Tyrnyauz // Selected works. Volume 1. Adyghe toponymy. - Nalchik: Elbrus, 2000. - P. 401. - ISBN 5-7680-1434-9. - Tverdy A.V.

Tyrnyauz // The Caucasus in names, titles, legends: experience of a toponymic dictionary. - Krasnodar: Platonov I., 2008. - P. 320. - ISBN 978-5-89564-044-9. - Tyrnyauz. General information (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Retrieved May 13, 2014. Archived May 13, 2014. - A railway will be built between Tyrnyauz and the village of Soldatskaya (Russian). 07kbr.ru

. Date accessed: October 7, 2021. - Rostec's subsidiary plans to resume tungsten mining in the Kabardino-Balkaria region at the end of 2023 (Russian). Expert YUG

. Date accessed: November 19, 2021. - “Tyrnyauz tragedy”, newspaper “Balkaria”, No. 2 (August 2000) (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Retrieved November 2, 2011. Archived March 1, 2010. - Russian Emergency Situations Ministry. Elimination of the consequences of mudflows in the city of Tyrnyauz (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Date accessed: June 21, 2021. Archived June 21, 2021. - Mudflow in July 2000. An eyewitness account. (Russian). www.scientific.ru

. Date accessed: October 7, 2021. - ↑ 123456789101112

People's encyclopedia "My City". Tyrnyauz - All-Union Population Census of 1970 The size of the urban population of the RSFSR, its territorial units, urban settlements and urban areas by gender. (Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Access date: September 25, 2013. Archived April 28, 2013.

- All-Union Population Census of 1979 The size of the urban population of the RSFSR, its territorial units, urban settlements and urban areas by gender. (Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Access date: September 25, 2013. Archived April 28, 2013.

- All-Union population census of 1989. Urban population (undefined)

. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. - All-Russian population census 2002. Volume. 1, table 4. Population of Russia, federal districts, constituent entities of the Russian Federation, districts, urban settlements, rural settlements - regional centers and rural settlements with a population of 3 thousand or more (unspecified)

. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. - The size of the permanent population of the Russian Federation by cities, urban-type settlements and regions as of January 1, 2009 (unspecified)

. Retrieved January 2, 2014. Archived January 2, 2014. - Population of the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic by settlement according to the results of the 2010 All-Russian Population Census (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Access date: September 21, 2014. Archived January 2, 2014. - Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities. Table 35. Estimated resident population as of January 1, 2012 (unspecified)

. Retrieved May 31, 2014. Archived May 31, 2014. - Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2013. - M.: Federal State Statistics Service Rosstat, 2013. - 528 p. (Table 33. Population of urban districts, municipal districts, urban and rural settlements, urban settlements, rural settlements) (undefined)

. Retrieved November 16, 2013. Archived November 16, 2013. - Table 33. Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2014 (unspecified)

. Access date: August 2, 2014. Archived August 2, 2014. - Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2015 (unspecified)

. Access date: August 6, 2015. Archived August 6, 2015. - Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian) (October 5, 2018). Date accessed: May 15, 2021. Archived May 8, 2021.

- Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian) (July 31, 2017). Retrieved July 31, 2021. Archived July 31, 2021.

- Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian). Retrieved July 25, 2018. Archived July 26, 2021.

- Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian). Date accessed: July 31, 2019. Archived May 2, 2021.

- Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (Russian). Date accessed: October 17, 2021. Archived October 17, 2021.

- taking into account the cities of Crimea

- https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/bul_Chislen_nasel_MO-01-01-2021.rar Population of the Russian Federation by municipalities as of January 1, 2021 (1.85 Mb, 07/30/2021)

- Volume 3. Table 4. Population by nationality and Russian language proficiency by municipalities and settlements of the KBR (undefined)

(inaccessible link). Date accessed: June 21, 2021. Archived March 6, 2021. - Volume 1. Table 2.2 Population of the CBD by age groups and gender (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Date accessed: June 21, 2021. Archived October 1, 2021. - Katya Li: biography (Russian). www.woman.ru

. Access date: October 13, 2021. - Where did the singer Ekaterina Lee from the group “Factory” (Russian) go? Yandex Zen |

Blogging platform . Access date: October 13, 2021. - ↑ 1 2

Anatoly Safronov.

The transcendental city is sixty years old // Kabardino-Balkarian Pravda, June 10, 2015 (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Retrieved July 4, 2021. Archived July 4, 2021. - M. I. Tsybulsky. Vladimir Vysotsky in Crimea // Vladimir Vysotsky. Catalogs and articles (undefined)

.

v-vysotsky.com

. Date accessed: October 7, 2021.

Excerpt characterizing Tyrnyauz

Late at night, when everyone had left, Denisov patted his favorite Rostov on the shoulder with his short hand. “There’s no one to fall in love with on a hike, so he fell in love with Tsa’ya,” he said. “Denisov, don’t joke about this,” Rostov shouted, “this is such a high, such a wonderful feeling, such... - I feel, I feel, I share and approve...” “No, you don’t understand!” And Rostov got up and went to wander between the fires, dreaming about what happiness it would be to die without saving a life (he did not dare to dream about this), but simply to die in the eyes of the sovereign. He really was in love with the Tsar, and with the glory of Russian weapons, and with the hope of future triumph. And he was not the only one who experienced this feeling in those memorable days preceding the Battle of Austerlitz: nine-tenths of the people of the Russian army at that time were in love, although less enthusiastically, with their Tsar and with the glory of Russian weapons. The next day the sovereign stopped in Wischau. Life physician Villiers was called to him several times. News spread in the main apartment and among the nearby troops that the sovereign was unwell. He did not eat anything and slept poorly that night, as those close to him said. The reason for this ill health was the strong impression made on the sensitive soul of the sovereign by the sight of the wounded and killed. At dawn on the 17th, a French officer was escorted from the outposts to Wischau, who had arrived under a parliamentary flag, demanding a meeting with the Russian emperor. This officer was Savary. The Emperor had just fallen asleep, and therefore Savary had to wait. At noon he was admitted to the sovereign and an hour later he went with Prince Dolgorukov to the outposts of the French army. As was heard, the purpose of sending Savary was to offer a meeting between Emperor Alexander and Napoleon. A personal meeting, to the joy and pride of the entire army, was denied, and instead of the sovereign, Prince Dolgorukov, the winner at Wischau, was sent along with Savary to negotiate with Napoleon, if these negotiations, contrary to expectations, were aimed at a real desire for peace. In the evening Dolgorukov returned, went straight to the sovereign and spent a long time alone with him. On November 18 and 19, the troops made two more marches forward, and the enemy outposts retreated after short skirmishes. In the highest spheres of the army, from midday on the 19th, a strong, fussily excited movement began, which continued until the morning of the next day, November 20, on which the so memorable Battle of Austerlitz was fought. Until noon on the 19th, movement, lively conversations, running around, sending adjutants were limited to one main apartment of the emperors; in the afternoon of the same day, the movement was transmitted to Kutuzov’s main apartment and to the headquarters of the column commanders. In the evening, this movement spread through the adjutants to all ends and parts of the army, and on the night of the 19th to the 20th, the 80 thousandth mass of the allied army rose from their sleeping quarters, hummed with conversation and swayed and began to move in a huge nine-verst canvas. The concentrated movement that began in the morning in the main apartment of the emperors and gave impetus to all further movement was similar to the first movement of the middle wheel of a large tower clock. One wheel moved slowly, another turned, a third, and the wheels, blocks, and gears began to spin faster and faster, chimes began to play, figures jumped out, and the arrows began to move regularly, showing the result of the movement. As in the mechanism of a watch, so in the mechanism of military affairs, the once given movement is just as irresistible until the last result, and just as indifferently motionless, the moment before the transfer of movement, are the parts of the mechanism that have not yet been reached. The wheels whistle on the axles, clinging with teeth, the rotating blocks hiss from the speed, and the neighboring wheel is just as calm and motionless, as if it is ready to stand for hundreds of years with this motionlessness; but the moment came - he hooked the lever, and, submitting to the movement, the wheel crackled, turning and merged into one action, the result and purpose of which was incomprehensible to him. Just as in a clock the result of the complex movement of countless different wheels and blocks is only the slow and steady movement of the hand indicating the time, so the result of all the complex human movements of these 1000 Russians and French - all the passions, desires, remorse, humiliation, suffering, impulses of pride, fear , the delight of these people - there was only the loss of the Battle of Austerlitz, the so-called battle of the three emperors, that is, the slow movement of the world historical hand on the dial of human history. Prince Andrei was on duty that day and constantly with the commander-in-chief. At 6 o'clock in the evening, Kutuzov arrived at the main apartment of the emperors and, after staying with the sovereign for a short time, went to see Chief Marshal Count Tolstoy. Bolkonsky took advantage of this time to go to Dolgorukov to find out about the details of the case. Prince Andrei felt that Kutuzov was upset and dissatisfied with something, and that they were dissatisfied with him in the main apartment, and that all the persons in the imperial main apartment had the tone of people with him who knew something that others did not know; and that’s why he wanted to talk to Dolgorukov. “Well, hello, mon cher,” said Dolgorukov, who was sitting with Bilibin over tea. - Holiday for tomorrow. What's your old man? out of sorts? “I won’t say that he was out of sorts, but he seemed to want to be listened to.” - Yes, they listened to him at the military council and will listen to him when he speaks his mind; but it is impossible to hesitate and wait for something now, when Bonaparte fears more than anything else a general battle. -Have you seen him? - said Prince Andrei. - Well, what about Bonaparte? What impression did he make on you? “Yes, I saw it and was convinced that he was afraid of a general battle more than anything else in the world,” Dolgorukov repeated, apparently valuing this general conclusion he had drawn from his meeting with Napoleon. – If he were not afraid of battle, why would he demand this meeting, negotiate and, most importantly, retreat, while retreat is so contrary to his entire method of waging war? Believe me: he is afraid, afraid of a general battle, his time has come. This is what I'm telling you. - But tell me how he is, what? – Prince Andrey asked again. “He is a man in a gray frock coat, who really wanted me to say “Your Majesty” to him, but, to his chagrin, he did not receive any title from me. This is the kind of person he is, and nothing more,” answered Dolgorukov, looking back at Bilibin with a smile. “Despite my complete respect for old Kutuzov,” he continued, “we would all be good if we waited for something and thereby gave him a chance to leave or deceive us, whereas now he is surely in our hands.” No, we must not forget Suvorov and his rules: do not put yourself in the position of being attacked, but attack yourself. Believe me, in war, the energy of young people often shows the path more accurately than all the experience of the old cunctators. – But in what position do we attack him? “I was at the outposts today, and it is impossible to decide where exactly he is standing with the main forces,” said Prince Andrei. He wanted to express to Dolgorukov his plan of attack that he had drawn up. “Oh, it doesn’t matter at all,” Dolgorukov quickly spoke, standing up and revealing the card on the table. - All cases are foreseen: if he stands at Brunn... And Prince Dolgorukov quickly and clearly explained the plan for Weyrother’s flank movement. Prince Andrei began to object and prove his plan, which could be equally good with Weyrother’s plan, but had the drawback that Weyrother’s plan had already been approved. As soon as Prince Andrei began to prove the disadvantages of him and the benefits of his own, Prince Dolgorukov stopped listening to him and absentmindedly looked not at the map, but at the face of Prince Andrei. “However, Kutuzov will have a military council today: you can express all this there,” said Dolgorukov. “That’s what I’ll do,” said Prince Andrei, moving away from the map. - And what are you worried about, gentlemen? - said Bilibin, who had been listening to their conversation with a cheerful smile and now, apparently, was about to make a joke. – Whether there is victory or defeat tomorrow, the glory of Russian weapons is insured. Apart from your Kutuzov, there is not a single Russian commander of the columns. Chiefs: Herr general Wimpfen, le comte de Langeron, le prince de Lichtenstein, le prince de Hohenloe et enfin Prsch... prsch... et ainsi de suite, comme tous les noms polonais. [Wimpfen, Count Langeron, Prince Liechtenstein, Hohenlohe and also Prishprshiprsh, like all Polish names.] - Taisez vous, mauvaise langue, [Hold your evil tongue.] - said Dolgorukov. – It’s not true, now there are already two Russians: Miloradovich and Dokhturov, and there would be a 3rd, Count Arakcheev, but his nerves are weak. “However, Mikhail Ilarionovich, I think, came out,” said Prince Andrei. “I wish you happiness and success, gentlemen,” he added and left, shaking hands with Dolgorukov and Bibilin. Returning home, Prince Andrei could not resist asking Kutuzov, who was silently sitting next to him, what he thought about tomorrow’s battle? Kutuzov looked sternly at his adjutant and, after a pause, answered: “I think that the battle will be lost, and I told Count Tolstoy so and asked him to convey this to the sovereign.” What do you think he answered me? Eh, mon cher general, je me mele de riz et des et cotelettes, melez vous des affaires de la guerre. [And, dear general! I’m busy with rice and cutlets, and you are busy with military affairs.] Yes... That’s what they answered me! At 10 o'clock in the evening, Weyrother with his plans moved to Kutuzov's apartment, where a military council was appointed. All the commanders of the columns were requested to see the commander-in-chief, and, with the exception of Prince Bagration, who refused to come, everyone appeared at the appointed hour. Weyrother, who was the overall manager of the proposed battle, presented with his liveliness and haste a sharp contrast with the dissatisfied and sleepy Kutuzov, who reluctantly played the role of chairman and leader of the military council. Weyrother obviously felt himself at the head of a movement that had become unstoppable. He was like a harnessed horse running away downhill with its cart. Whether he was driving or being driven, he did not know; but he rushed as fast as possible, no longer having time to discuss what this movement would lead to. Weyrother that evening was twice for personal inspection in the enemy’s chain and twice with the sovereigns, Russian and Austrian, for a report and explanations, and in his office, where he dictated the German disposition. He, exhausted, now came to Kutuzov. He, apparently, was so busy that he forgot to even be respectful to the commander-in-chief: he interrupted him, spoke quickly, unclearly, without looking into the face of his interlocutor, without answering the questions asked of him, was stained with dirt and looked pitiful, exhausted, confused and at the same time arrogant and proud. Kutuzov occupied a small noble castle near Ostralitsy. In the large living room, which became the office of the commander-in-chief, gathered: Kutuzov himself, Weyrother and members of the military council. They were drinking tea. They were only waiting for Prince Bagration to begin the military council. At 8 o'clock Bagration's orderly arrived with the news that the prince could not be there. Prince Andrei came to report this to the commander-in-chief and, taking advantage of the permission previously given to him by Kutuzov to be present at the council, remained in the room. “Since Prince Bagration will not be there, we can begin,” said Weyrother, hastily getting up from his place and approaching the table on which a huge map of the surrounding area of Brünn was laid out. Kutuzov, in an unbuttoned uniform, from which, as if freed, his fat neck floated out onto the collar, sat in a Voltaire chair, placing his plump old hands symmetrically on the armrests, and was almost asleep. At the sound of Weyrother's voice, he forced his only eye open. “Yes, yes, please, otherwise it’s too late,” he said and, nodding his head, lowered it and closed his eyes again. If at first the members of the council thought that Kutuzov was pretending to be asleep, then the sounds that he made with his nose during the subsequent reading proved that at that moment for the commander-in-chief it was about much more important than the desire to show his contempt for the disposition or for anything else. be that as it may: for him it was about the irrepressible satisfaction of a human need - sleep. He was really asleep. Weyrother, with the movement of a man too busy to waste even one minute of time, looked at Kutuzov and, making sure that he was sleeping, took the paper and in a loud, monotonous tone began to read the disposition of the future battle under the title, which he also read: